Founder, entrepreneur, and angel, Richard Lane, explains his experience investing in companies such as Alice’s Table and The Jitterbug phone.

Highlights:

Sal Daher Introduces Richard Lane

"... The founder is in the business of discovering new territory, terra incognita. The angels and the board members are in the business of making sure that she doesn't run aground on well-known shoals..."

Alice's Table

"... She was helping women who were very much into floral arrangements to teach in-person classes in floral arrangement, and how to make a really beautiful floral arrangement. What her business did-- basically, she helped these women to run events. The women would use those tools in their network..."

"... As an angel investor board member, I go in and I say, "Are you on schedule? Great. Everything's good? I don't care about that. I'll look at that later. Tell me what is keeping you up at night. What is the first stumbling block?"

Richard's Entrepreneurial Career

"... One of the driving things I had since my childhood was, what happens when you die?"

Telephone Companies

"... It's a business that didn't exist. Before that, landlines were everything. It was everything, that was telephony was a landline..."

Pacific Telephone Company

The Jitterbug

"... A couple of things worth noting, a device around older people, needs to be looking at their user’s expectations. We're hardwired by the time we're 65 to think certain ways, to do certain traits..."

LifePod

Parting Thoughts to the Audience

ANGEL INVEST BOSTON IS SPONSORED BY:

Transcript of “The Promise of Age Tech”

Guest: Richard Lane

Sal Daher: I'm really proud to say that the Angel Invest Boston Podcast is sponsored by Purdue University Entrepreneurship and Peter Fasse, Patent Attorney at Fish & Richardson. Purdue is exceptional in its support of its faculty, faculty of its top five Engineering School in helping them get their technology from the lab out to the market, out to industry, out to the clinic. Peter Fasse is also a great support to entrepreneurs. He is a patent attorney specializing in microfluidics and has been tremendously helpful to some of the startups which I'm involved, including a startup came out of Purdue, Savran Technologies. I'm proud to have these two sponsors for my podcast.

[music]

Sal Daher Introduces Richard Lane

Welcome to Angel Invest Boston, conversations of Boston's most interesting angels. Today, we are privileged to have an angel investor and entrepreneur with us, Richard Lane.

Richard Lane: Hi, everyone. Great to be here.

Sal Daher: Rich Lane is a buddy of mine from Walnut Ventures, and he and I have invested in companies together. Rich has been a very important active person in Walnut, he's a treasure of Walnut for many years. Two younger guys showed up, one of these younger angels, and took up that mantle. Very grateful for Rich for volunteering for that faithless task of collecting the -- [laughs] – rounding up these members of cheapskate members New England angel group. $400 a year it's hard to collect. There's a lot of cheapskates in New England, but at the same time, they're very generous. That's the thing with New England types. They're both frugal and generous at the same time.

It's a wonderful paradox. Anyway, Rich, I thought that in this conversation we will organize it this way. Let's talk about some of the startups because everybody wants to hear about startups. In the second half, we can start getting into your entrepreneurial journey, companies that you built. By the way, Richard Lane, if you've heard Jitterbug, the telephone for older people. Rich was the COO of Jitterbug. He's been in that space, and he knows tons and tons and tons about this stuff. He's a graduate of University of Pennsylvania, MBA from UPenn. Anyway, Rich, let's talk startups. What startups are in your mind right now, at this moment?

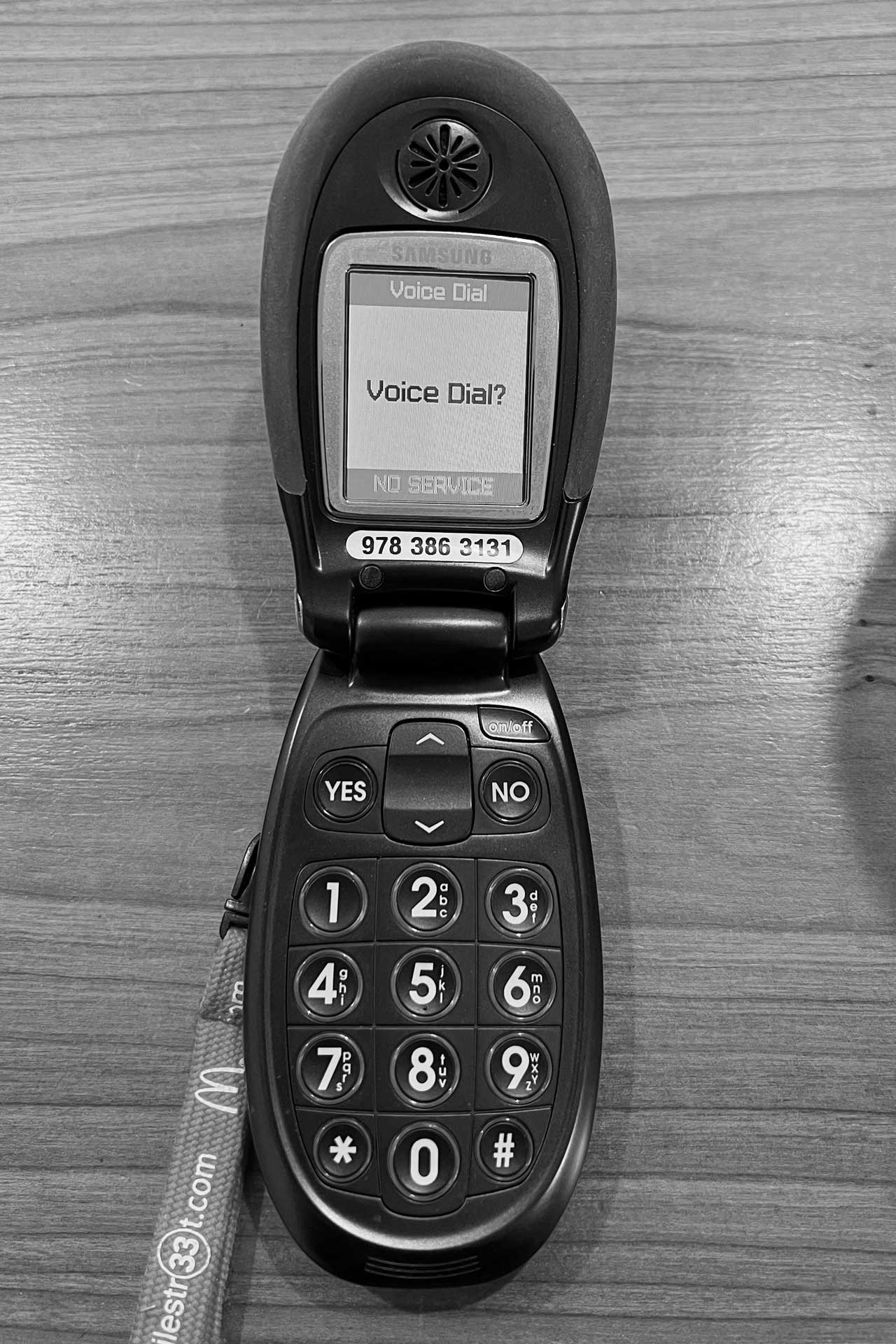

Richard Lane: I'm very interested in a number of startups that are in the disruptive space in changing the way our economy goes, as I'm most focused on the older space. Starting with, as you mentioned, I brought my prop, the original Jitterbug.

Sal Daher: Rich, send me some graphic assets related to the Jitterbug. If you have stills of the Jitterbug or whatever.

Richard Lane: I do.

Sal Daher: Afterwards, we can record a video of you showing the Jitterbug.

Richard Lane: I got two props, that one and that.

Sal Daher: Oh my gosh, a brick.

Richard Lane: This is not only the brick, this is the copy of the original phone that made the first call in the history of the world.

Sal Daher: Oh, man, this is going to be a cool-- props are great for the video. It's a 16, 20-second video that we have that runs on LinkedIn, great effect. My business partner, Bob Smith, when I first joined back in 1988 he had one, it was a Motorola brick. It was a little smaller than that thing that you're holding in your hand. By the way, listeners, we're going to have pictures of this, and there's going to be a video of this showing you the props. You're going to be able to see the Jitterbug and the brick. Anyway, Rich, you're talking about disruption in the older space.

Richard Lane: Let me start off with one of the non-elder block companies, and then I'll talk a little about the elder. One of the companies I'm involved with as an angel investor is a company called Adelante Shoes. Adelante looked at the-- it's started by a grad student at Tufts. It's been funded by, I think, besides me another name is Steve Ritchie who used to be with Liberty Ventures. I can't remember their latest flagship, and I think the Cole Haan family.

Anyway, the biggest cost in shoes similar to Warby Parker and others is the cost of inventory and stocking it. With our situation in the shoe industry from the January till September, they're filling warehouses, carrying the cost of inventory, and they have to make in every color, every size to get through. With Adelante, what we do is we just inventory the leather.

When you order pair of shoes, and when we do our videos I can show some of those. What we do is you place an order with your credit card, you choose what color of leather you want, what color size. If you're two feet or different sizes you do it. You choose which fits you. You can change the colors around any way you want, and you put your credit card down. We now got the money.

Our cobblers in Guatemala get paid twice what the going rate in Guatemala is. They hand-make it. They send you an intro to your cobbler. Then your cobbler says, "You want to watch me make your shoes?" He takes a little video of him making the shoes, literally. I made a custom color, so I saw mine because nobody else ever did it that color. You watch it. Within 7 to 10 days it's in your home, money-back guarantee.

Sal Daher: Phenomenal.

Richard Lane: We're able to produce the quality of shoes of $500 shoes for $300.

Sal Daher: Wow. Man, I'm on a market for shoes right now. I'm going to try Adelante.

Richard Lane: Adelante, when we're not on I'll give you the code for a discount as my friend. I get an automatic discount.

Sal Daher: Oh, jeez.

[laughter]

Richard Lane: It's great. First time I wore a pair to a trade show the day I got them, I was on my feet for five hours and my feet felt great. Well constructed, I've had them now. I originally screened them for Walnut. Arrigo and I did that.

Sal Daher: Arrigo Bodda, who's been on the podcast. He is Italian, former Head of Human Resources at U.S. Steel, I guess. He was a senior manager in Human Resources, U.S. Steel, retired. He's now an angel investor, an Italian.

"... The founder is in the business of discovering new territory, terra incognita. The angels and the board members are in the business of making sure that she doesn't run aground on well-known shoals..."

Richard Lane: We didn't bring it to Walnut for two reasons. One is Arrigo wasn't Italian enough looking, a born American. The bigger reason is-- this is where it gets back to angel investing is we didn't think that a group like Walnut would be interested in consumer product. It's very hard to build consumer brands and get traction. I am an exception because I built my career in cellular phones and other technologies sold to the consumer. I know how to build brands and how to be successful at it.

I tend to invest in those companies where the CEO can call me and say, "Rich, what do you think?" That happened when we were closing our first round of money. Peter, the CEO, calls me in a negotiation. He got stamped. He didn't know how to reply. Because he keeps in close contact he was down in Guatemala talking to a strategic, and he didn't know how to deal with it. Called me, I sketched out something, he went back in and we closed the deal for a quarter of a million dollar investment after a 20-minute phone call. That's where an angel really adds value, is having been there, having sat there so many times on both sides of the fence.

I've done 10 startups, so I know as an entrepreneur what questions are going to be asked. It doesn't matter if it's shoes. I've done a solar panel company, I'm doing-- as a chairman of a CRM company which I'm an angel investor in. It doesn't matter what the company is. The questions are almost always the same, go-to-market, how you provide the service, logistics, and what makes you different than someone else.

Sal Daher: Very true. The founder is in the business of discovering new territory, terra incognita. The angels and the board members are in the business of making sure that she doesn't run aground on well-known shoals. There's a reef over here-- while you're exploring unknown land I know there's a reef here. I'm just letting you know. O r asking questions also, where you hear, "Oh jeez, I heard there's a reef here. Are you aware of this?" We're like the stuff that's known. We can help startups with the stuff that's unknown-- it's for them to discover. We have to give them the room and the freedom to discover the unknown, but at the same time just make sure that they don't trip up on stuff that's pretty obvious and pretty mundane.

Richard Lane: Believe it or not, for people to think about it, it is not that different than a well-run large company. If you read Ed Whitacre's biography of how he turned around Southwestern Bell and bought AT&T and made it a success. I have had the pleasure of meeting Ed over the years. Ed took the principle of his board as not people who are coming to grade his paper.

They're the teachers and they're grading your paper, and they're going to yell at you if you didn't do it. A well-run board, whether it's an angel board or a corporate board, and having been on both is to be advisors. Bring insight to the CEO because the CEO has got his-- mainly an entrepreneur we keep telling them, stay focused, keep your eye on the ball, pay attention to what you're doing. Focus, focus, focus.

We as angel investors and board members, again, public or private, we have to give them the broader view. What are other people doing in the sector? What is some of the lessons learned? What are the questions that people are asking today? COVID comes, what is the change? Which will lead me to another company I invested Alice's Table in a minute? The board, the advisors, formal or informal need to provide that CEO with the guidance-- not guidance, wrong word, with some insight.

They make the decisions. Our job is to provide them with gray hair, experience-- even with older, I'm chairman of a company where they used to-- all the entrepreneurs are in their '50s but they've had not done the scope. They've done one or two businesses, they haven't seen the number of dozens of companies, Sal, that you and I see in our lifetime.

Sal Daher: Yes, there's a different-- I'm an investor in a company that was extremely, extremely promising. They've been on the podcast a few times and they hit a reef, they hit a shoal. That was they had some unpaid obligations to employees, and the whole company just got blown out. That can happen and this is the stuff where having people who've been around the block a few times, a little bit of gray hair, they can tell.

I'm on a board of a company that had at one time ran that risk, but luckily there was an investor who was an attorney and he said, "Salary liabilities in Massachusetts are extremely serious. You need to watch those and you need to make sure you take care of that immediately because that can sink your company." Things like that, I sort of tripping on your shoelaces is the stuff that angels and board members can help founders with. As I said before, founders have to discover really the uncharted territory ahead. That's their business. Very good. Let's talk about Alice's Table.

Alice's Table

Richard Lane: Yes. Alice's table is an interesting company. I met years ago through -- we're fellow Penn alums. She came and presented to Walnut separate from me, and matter of fact I missed that meeting, so I didn't even know that she presented. She had won Shark Tanks.

Sal Daher: Yes. Eventually, she was on Shark Tank after that, after she presented a Walnut. I invested in Alice's Table as well. Yes, so please continue.

Richard Lane: She had a great concept of helping women get into back into the business marketplace once their kids went off to school. That was the premise. How do you help women? That's a secondary besides elder care, helping women get into business is something that's been a lifelong journey that me and my cousins have been working with, led by one of my eldest cousin, who's a woman. Anyway, so it struck a chord with me. How do you help women get back into life? I've helped my wife do it. She's been teaching for 12 years, but she was a lawyer before she had kids.

Sal Daher: Rich but before we get into this, I just want to mention here that as a father of two daughters who are both professionals. For me, it is very much in my mind the importance of women being able to get back into professional life after having children. Because if they want to have children it really makes sense for them to have children relatively early. It's just like the earlier the better, more likely they're going to have and so forth, and that's the time when you're building a career.

This conflict between having a family and having a career is particularly acute if they want to start a family. If you're a physician, for example, one of my daughters is a physician, you don't have any choice. You have to be full-tilt in your career for 20, 30 years before you can think about doing anything else. You invariably you're going to have a very hectic life juggling career and children.

I wonder if there could be another path, for example, we've had on this podcast. One Lucinda Linde, who she had a career as a VC and a consultant and did a lot of work. She took off many years because she wanted to be home with her boys, and then she came back after that and retooled as a data scientist. That's an interesting example, a second career that she had and she realized how important it was for her. I think the venture fund that she was involved with had been fully invested and she had a natural pause.

She could get involved in a new fund, or she could get involved with her five and seven year old who were very fascinating to her at the time. She chose to do that as an option. What you're talking about here is a very, very great interest to me because I want my daughters to have those options if it's what they want to do. Please continue, Rich, on Alice’s Table. Then just say Lucinda Linde-- if anybody wants to listen, I interviewed her Engineer, VC, Consultant, Angel. You can look up L-I-N-D-E, she's a tremendous person.

Richard Lane: A good friend of all of ours.

Sal Daher: Yes, she's awesome. It's one of those people you can't help but smile when she's around, right?

Richard Lane: Yes.

Sal Daher: Lights up the room. Anyway, Rich, please continue.

Richard Lane: Okay. When I heard Alice-- her name is Alice Lewis-- what she was looking to do resonated. Because my wife had our two boys while she was in law school, she got out. I remembered her being recruited by a firm that says, "The problem when your wife has-- how many female partners are there?" They say, "Oh, none." She said, "Why?" They said, "Oh, because they all want to get pregnant and don't want to work."

[laughter]

My wife at the time was four months pregnant. She walks out, I'm sitting in the-

Sal Daher: Cavemen.

Richard Lane: -parking lot. She just said, "What the--" I won't use the words in the podcast.

Sal Daher: Caveman Lawyer.

Richard Lane: That was the mindset back in the late '80s. I swore that my wife would do what she wanted. We came up here, she's decided not to stay in the practicing. Was a mom and then when she went back she said, "I want to fight." I said, "You, a young kid, again." I'm up against all the 30-somethings willing to kill themselves. She was at the time 50 and she said, "I can't do that."

Sal Daher: No.

"... She was helping women who were very much into floral arrangements to teach in-person classes in floral arrangement, and how to make a really beautiful floral arrangement. What her business did-- basically, she helped these women to run events. The women would use those tools in their network..."

Richard Lane: It was a new career path, so she learned to teach kids with dyslexia how to read. She does that now full-time and she's been doing it for 15 years. The point is with Alice's was she wanted to come up with a way to allow these people to rebuild their quality of their life. The way to get into a business environment and network and get back on the track. A lot of women do this through network marketing, and they don't have tools. I'm actually the chairman of a company building a toolkit for these women.

When they want to get into network marketing they have the structure and the technology that will allow them to do this without having to just hit their head against the wall. Because 90-something percent of women who try to go into it go into real estate network marketing and fail at both. When I saw Alice she did a great job, she really was getting it off the ground then COVID hit.

Sal Daher: Let's talk about the initial instantiation of Alice's Table. What Alice was doing-- this is before COVID. She was helping women who were very much into floral arrangements to teach in-person classes in floral arrangement, and how to make a really beautiful floral arrangement. What her business did-- basically, she helped these women to run events. The women would use those tools in their network. I can tell you, I have a friend who is a private banker, at a very high-end private bank.

She heard about this and she loved it. She used to hold these events with her private banking clients. She would sponsor-- she would hire Alice's Table and there would be an Alice's Table person who would teach a flower arrangement class to these high-net-worth women who are the clients of my friend, this high-net-worth banker. She thought it was extremely, extremely powerful and she came to me. She was like talking about it-- it was kind of an accident, she discovered I was an investor. Because it was so brilliant.

It's just there is a tremendous need for that, and it's very, very rewarding for everybody involved, for the people who are taking the classes, and for the women who are teaching the class. Because usually, it's a part-time thing. They might be doing this for 10 hours a week or 20 hours a week. It's event, they have flexibility about arrangements and so forth. What Alice's Table provided was the infrastructure. I think that everything like the flowers, the scissors, the--

Richard Lane: Everything was kitted in a box.

Sal Daher: Right, right. That was a very interesting path upwards, and so interesting that they were invested in by the Sharks in Shark Tank. They were on Shark Tank.

Richard Lane: They were going on a great trajectory, both financially and on their passion of accomplishing something, and then COVID hit. When COVID hit, they could no longer hold these in-person sessions, and that became what now situation. What I was super impressed with is Alice said, "People really like the sessions. They can't come in, how can I save my investors their money? How can I keep this business alive?"

She pivoted to grabbing the high-end trainers, the people really knew how the better performers or the trainer of the trainers, and started running webinars where people would sign up. She would drop ship the kit to the person, and they would do it over a Zoom-type environment. As an investor, I was super impressed the fact that she was able to pivot the business so quickly in a catastrophic pandemic environment, and increased revenue instead of decreasing revenue. Very impressive.

She had initially partnered with KaBloom. She then partnered with 1-800-Flowers. That allowed her to expand beyond flowers. They were doing gift baskets and so forth by partnering with Harry & David, Shari's Berries, all the different product lines within 1-800-Flowers. A year ago now, as the two of us, Sal remember is 1-800 who then had made an investment, wanted to buy the company, because they wanted to scale it and they were drop shipping everything.

They said, "Hey, we can really make this a lot bigger business if we're doing the provisioning." One of the negatives was that Alice got herself by being so successful, her cash flow became very negative, and 1-800-Flowers she owed them a lot of money. It was just the timing, that's killed a lot of flower companies is the timing between when you get your money and when you have to pay for the flowers.

Anyway, so she then sold the company to 1-800, and she continues and I believe -- I haven't spoken to her in a couple of months, but I believe she's still running that business unit there. I know she's had two kids since she started this business and it hasn't lost-- I think they're two girls, I'm not sure. I know one was a girl. She's very much living the dream. She plans to do another startup.

Sal Daher: Rich, before you take her side, I just want to fill in the gaps here. Alice Lewis, when we invested, she was Alice Rossiter. She got married, changed her name, and now she is Alice Lewis. Yes, I am ready to write checks to Alice again. Even though I haven't been writing checks in that space, I'm going to feel very tempted to write a check to Alice if she does something in the future because she's just such an incredible dynamo.

She crosses her Ts, dots the Is, she really keeps people informed. She just gives it all. By the way, she's been on the podcast twice. I invite listeners to the original podcast with Alice, which is from Techstars to Shark Tank. She did a COVID update, which brought us to date on her COVID pivot. Really, an exceptional founder. We've had two really exceptional women that we've talked about on this podcast already. Our friend and the angel investor, Lucinda Linde, VC, engineer, and investor. Alice Lewis, founder of Alice's Table, Shark Tank, and Techstars alumna. Anyway, Rich, so please continue.

Richard Lane: One of the things that I find which us angels understand different than invest venture capitalists and what they call themselves professional investors, which I don't think there is any more professional than we are because we're writing the checks and they're writing checks with our money in it. Anyway, I look at an entrepreneur, and unlike somebody who says, "I want to see what you did and the life of the company, and what you built and everything else."

There's very few people who are going to be like Neil Blumenthal who built Warby Parker from the concept in the grants class thinking going public and being a very wealthy man. Interesting story and if people are interested, we can tell you where that's been written up. Generally, people are good at different phases of a company. When I look at an angel investor, I'm not interested that they build a company from $10 million to $100 million. I really don't. I want to see can that angel investor build it from zero to $10 million. I'd like to know the other, but if they can get it from zero to $10 million-

Sal Daher: Founder or angel investor?

Richard Lane: Yes.

Sal Daher: Founder.

"... As an angel investor board member, I go in and I say, "Are you on schedule? Great. Everything's good? I don't care about that. I'll look at that later. Tell me what is keeping you up at night. What is the first stumbling block?..."

Richard Lane: I'm saying when a founder who starts a company or brought in like I was one of "The founder of Jitterbug," I was brought in because I knew how to take a revision and build it into something. I took the vision of how do we make a cellphone for the older market because only 28% of the market at the time olders use cellphones. We looked at it and said, "Okay. What do we need to do from the bottom up to make this product something that people are going to care about?" I came in and I told Arlene, the founder, I will come in and I will take your vision and get you to revenue. Then I don't want to move to California, I will then get somebody who knows how to get it from its small revenue to scale it to hundreds of millions.

Sal Daher: This is really, really important, the zero to one and one to N distinction that Peter Thiel talks about. I think we need to understand as the English say, "There are horses for courses. There are founders and there are angels for particular stages in a company." This is also very true in the life sciences. I'm trying to build out a niche for Life Science Angels in taking academic founders to the point where they can get a collaboration with a strategic and then proceed from there. Maybe at that point they might get other types of funding. You're absolutely correct, we have to look at the phases. There just simply not enough VCs to be doing all the stuff that has to be done.

Richard Lane: The VCs generally and there's some fabulous VCs I worked with over the years, but there's been some real terrible ones also. Some who have never worked in business, never had to be responsible for P&L or balance sheet, and think they had the answers. Some of them listen to their entrepreneurs and those are the good ones, the Paul Maeders of the world from Highland Capital. These are some great people. John Brooks who was the founder of Prism. These guys were operators as well as running a fund.

I admire these gentlemen a great deal. I can give you some women who've done the same. What I find is, and I get this a lot, I get VCs who call me and say, "Rich, I don't know anything about this business from the bottom up. How can you help me understand it? How can you help me help my entrepreneur?" I wrote a paper on this once. VCs walk into a-- a little tangent here.

They walk into a meeting with their portfolio and they're going in with the idea, "Please, tell me everything is okay, so I can go back to my partners in the partner meeting and say, "It's on track." That's all I want to hear. I don't want to hear anything else. Keep me blinking. Lie to me, do whatever you want, but keep me so I don't have to be a good before my partners."

Then the entrepreneur looks at it as, "Oh, God. He's coming to yell at me. I better make sure I can do spin control. I got to do--" I've actually wrote a paper on this and gave a seminar on it once. That is the most destructive way to approach it. That's why early stage are much better with angels because we never go in and say, "Tell me everything's okay." We go in and say, "How can we help you?"

Sal Daher: Yes, I don't want to hear about problems. I want to hear good results, so I can report to my limited partners and my partners and the LPs.

Richard Lane: As an angel investor board member, I go in and I say, "Are you on schedule? Great. Everything's good? I don't care about that. I'll look at that later. Tell me what is keeping you up at night. What is the first stumbling block? What are you doing about cash flow? What's your debt note look like? Is it one that can be called because you had bad convenance or is it something that's linked to revenue and you just pay down this revenue?" I mean lots of people may say debt is bad. Bad debt is bad. Good debt is good. We know that VCs don't have a clue.

Sal Daher: Debt is a tool like a shovel. It can be used to very constructive ends, planting things, and so forth. It can also be used to break things. It's a tool. Rich, in interest of format here, let's think if there are any other thoughts that you want to have about the startups that you've invested in. Because I want to go into the second half of the interview, which is your angel journey. How you got to be where you are. Do you want to wrap up right now what you're saying about startups? We can move on to the second half.

Richard Lane: I think we're good to move to the next half because the next half will about my running companies.

Sal Daher: Be a very different perspective. Before we go onto that, I just want to put in a plug for the podcast. I want to invite listeners. This podcast is created for you to learn, for me to learn, and for you to learn. I have people who know tons more about building companies than I do, such as Rich who's been very kind to make an hour available from his really busy schedule to be on the podcast.

The point here is that these conversations might be helpful to someone out there and you never know when. It's kind of a hear-or-miss kind of thing. Not every podcast is going to be useful to every person. We'd like to have the widest possible listenership. The way you can help us get discovered, there's number one, follow us. It's not subscribe anymore, it's follow.

There's a little plus button on your Apple Podcast app. I don't know exactly how it works in other environments. Also, leave a review. A written review is extremely powerful. You can be very candid on your written review. You can say, "Oh, that Sal just talks too much, but he does have interesting guests," for example. As long as you give us a five-star rating-- don't mess us up on the rating, be candid. You can be as candid as you want on the written reviews.

Doesn't have to be long. Written reviews are really valuable because the algorithm says, oh, somebody has taken time to write. This must be a very important review. Anyway, so consider doing that for us, subscribing and putting a rating, and also leaving a written review. Also, by the way, if you happen to have a really interesting compelling founder or angel that you'd like me to talk to, please let me know. Because I recently had a really great interview that came from a listener-- shout out to Sudhir Manda. Dr. Sudhir Manda, who connected me with Junaid Shaik, Dr. Shaik who has a fantastic device with $600,000, Rich.

This guy built a device to do blood smear tests to digitize blood smear tests, and to just tremendously improve the whole efficiency of that. This is $600,000 in India. He's repatriating the company to the US. A fascinating interview, Livo.AI. That came from a listener who is a tremendous guy, and who might also like to have on the podcast sometime. Some people can be shy a little bit, but if you have a startup or someone who would like to be on the podcast, please feel free to get in touch with me and let me know.

Richard Lane: Anyway, Rich, can I comment on your plug for a second?

Sal Daher: Sure, please.

Richard Lane: I, as somebody participating, I'm giving back for this stage of my life. Back to all the wonderful people who've helped me over the last 40 years of my career. I've had some incredible mentors, leaders in the several industries telecommunications. My goal here and why I'm doing this is how do I give back to the next generation. If in your review you have positive or negative comments, that's going to help me help you better.

Sal Daher: Awesome.

Richard Lane: You're not just doing it for ratings, you're also doing it so I can help you.

Richard's Entrepreneurial Career

Sal Daher: We only want five-star ratings, but the review be as candid as you want to be. Awesome. Rich, let's talk about your entrepreneurial career. You went to UPenn and then you went to Wharton-- graduated from Wharton, and you went to work in what space?

Richard Lane: I went to Wharton twice. I did Wharton undergrad, and then I went into the office products industry. This is my first product, and you see my names here, a stapler.

Sal Daher: What was the brand?

Richard Lane: Swingline.

Sal Daher: Swingline Staplers. Rich, we need graphic assets of all those three, okay?

Richard Lane: Okay. Now a moving theory for me when I got was went to business school was, I came from a family of entrepreneurs. I didn't want to go into the family business. I wanted to make a difference.

Sal Daher: What was the family business?

Richard Lane: My family business was a printing company. My grandfather had a printing and stationary company. When he died, my dad took it over. He made it into a business forms company. We had a paper company, an envelope company, a warehouse. The dream of my dad and uncle was it would be my business someday. Of course, I did not want to do a legacy product, and I didn't want to be third generation of company.

Sal Daher: This is just like my longtime business partner, my dear friend Robert P. Smith, whose father's business was collection law. He was a partner, at one time, Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He was a very respectable person. My business partner, Bob Smith, this is the '60s. Smithy wanted to go out and explore the world. He didn't want to work in his dad's collection law practice, but he was forced to go to law school.

His father was a little chagrin. Bob's adventures, Bob turned out to be a huge success in a very adventurous business. He used his legal training to become one of the top people who created the whole business of emerging markets. When you hear about emerging markets, think about Robert P. Smith and his father, David Smith. He gave a building to Bowdoin College, the Smith Center at Bowdoin College, in honor of his dad who went to Bowdoin.

They're very different people, very different perspective on things. His dad was a Republican, Bob was a Democrat. The '60s happened, so I understand that. [laughs] Smithy used to, "All the parakeet ads from The Boston Globe, that's my dad wanted me to be collecting a parakeet ads in the Boston Globe. I wanted to be off to Turkey collecting on debt that Bali gaming company held from the Turkish casinos. That was much more interesting than Mrs. McGillicuddy's parakeet ads in The Boston Globe."

[laughter]

Sal Daher: Please, continue, Rich.

Richard Lane: Anyway, I grew up in Manhattan. You also have the issue of everybody's got different businesses. I had an uncle who had a spice company. My grandfather had a fur company. I had another uncle who was a lawyer. By the way, think of lawyers as entrepreneurs because they're starting their own businesses.

Sal Daher: They have to get clients in. Smithy's father was definitely an entrepreneur, although he was a very stayed kind of entrepreneur. Anyway, you're right. In those days, physicians were not very entrepreneurial, because you just hung up a shingle and you had a practice. Whereas, today, in order to be an independent physician, you have to be a real entrepreneur. Anyway, please continue, Rich.

"... One of the driving things I had since my childhood was, what happens when you die?..."

Richard Lane: You may want to edit this out. One of the driving things I had since my childhood was, what happens when you die? I'm getting a little philosophical, but I'll show you why I did everything I did. My grandfather said to me, "Set me down." My dad had a brain tumor when I was six, so that's why this was such an issue. He said, "Hey, I can tell you what every religion tells you, but one only thing I can tell you can control is what you do on this earth, and what difference you make to people being a good father, good husband. Creating new things, being a good member of the community. That's what's going to live beyond you." That has been my mantra for 62 years.

Sal Daher: Rich, I would never take that out. That's extremely valuable. It's really important for us to understand that we have so much time to fulfill our potential, to do the best that we can to make the lives of people around us better. We don't have time to fool around, I think is a very important lesson. Please, continue.

Richard Lane: When I mentioned I went to Swingline Staplers and you said, "How does that fit with that vision you had?"

Sal Daher: Your father was in a very conventional business and you went to, oh, a real rocking business, Swingline Staplers.

Richard Lane: Let me tell you why I did it. I was hired by the CEO, which I'd met through a friend of my dad's. He said, "If you go back to the early '70s or the mid-'70s, everybody was talking about the paperless office. These new computers are coming and they're going to do away with paper. If we don't have paper, we don't need fasteners."

Sal Daher: How little we knew.

Richard Lane: I was hired to come up with a line of products that were not fascinating products. I did that and we came up with our business equipment division. I got promoted five times in three years. I didn't have anything to do with staplers after my first six months there when I came out with my first machine. We had bursters, declutters, folders, and all these types of equipment that traditionally big companies had for their mainframe computers.

They cost $50,000 for one of those things. When you got to mini computers that put out continuous checks, you would be in a situation where they couldn't afford that equipment. My research was I went to data room after data room after data room, doing market research, sitting and looking at what people did. What's interesting is you'd see there someone sitting there within the letter opener for three days cutting apart all those continuous checks. Didn't save a lot of money, a lot of time. Automation just said you didn't have to type it, but every check got cut, folded, and stuck in an envelope. I came up with a line of equipment that did that for hundreds of dollars instead of tens of thousands. Fast forward, I go to graduate school, I taught undergraduate marketing to pave my way and I got my degree in finance and I get recruited by AT&T to come in. Now you're going to say AT&T-

Sal Daher: Oh man.

Richard Lane: - that's a public utility.

Sal Daher: You rock and roller, you.

Richard Lane: I got hired.

Sal Daher: Rich, by the way it's so funny. This is the '70s and we're talking about the paperless desk and I'm sitting at my desk. You're surrounded by paper still. It's 2022.

Richard Lane: Yes. You don't have--

Sal Daher: How little we knew, 50 years later, we'd still have paper around.

Richard Lane: But what's interesting is I don't fasten it anymore, because after I'm done with it, I throw it away.

Sal Daher: That's true.

Telephone Companies

Richard Lane: I haven't bought a box of staples in 10 years. From a stapler company point of view, would've made a difference, but anyway, let's get to AT&T. When I got hired there, I got hired by the chief marketing officer of the company.

Sal Daher: AT&T, American Telephone and Telegraph. This is the phone company. This was at the monopoly phone company, the bell system.

Richard Lane: This is before they broke it up. This is 1981.

Sal Daher: Okay. For people who don't know this, until the breakup of AT&T in the '70s, they were a controlled monopoly meaning it's a public utility. They were run as a public utility like the light company. There was a commission that regulated the rates and everything else. You had a black phone, you had the choices. Towards the end, they were coming in with a princess phone and slight innovations and so forth, but it was basically a monopoly business that was broken up in the '70s and they created all these different businesses that had the local lines and the cell phones and so forth, I mean, explosion occurred.

Richard Lane: It didn't get broken up to till January 1st of 1984.

Sal Daher: '84, I'm sorry. 1984 I was thinking about the airlines, deregulated during the Carter administration. Okay. Please continue, Rich.

Richard Lane: Yes. The head of marketing came and talked to us at the Wharton Club, the Mark Wharton school. I was the president of the Marketing Association and he wished me good luck on my interview. I told him I wasn't interviewing. I can tell I spend an hour on this story, but anyway, he then convinced me to try with the commitment that I would only-- Arch Miguel was his name. He had been recruited from IBM and he said, "We need people like you." He gave me an offer that guaranteed I'd never have to do any other thing but new products.

What was my first product? Something that, this conversation is very reminiscent. My first product in 1981 was teleconferencing. My office did a picture phone meeting service, which was first introduced at the 1964 World's Fair in New York City and it was a fascination, so I did that and then all of a sudden somebody comes to me and says, "We can't do innovation well in this big company." There was 1.3 million employees. Think about that. We were a country onto our own. You talked about what generation in the phone company you were.

Sal Daher: People today cannot imagine this. This is a country. In those days, United States had, what? 200 million people? This is like half a percent of the entire population of the country worked for this company.

Richard Lane: Only worked within the United States.

Sal Daher: Yes. Only for in the United States. It would be like having a company with 3.5 million people just servicing the US. That's the scale. The armed forces in the United States don't get the 3 million people.

Richard Lane: They brought me in, and this is what I call my first third of my career was an entrepreneur. That means starting companies within big companies. They said, "Cellular is never going to take off if it's still within the big phone company. They formed a separate company. They moved it into a building, a small building, said you'll get fired if you ever go into corporate headquarters.

Sal Daher: Okay.

Richard Lane: They told 30 people together to start this thing. I was one of the 30 people.

Sal Daher: Basically it was like skunkworks.

Richard Lane: That's right. I was one of the 30 people, and God bless my wife was brought in from New York. We met at the copier our first day, and you guys are probably in the audience thinking, "What? Sexual harassment. Sexual rules."

Sal Daher: [laughs]

Richard Lane: No, this was something that was encouraged. We had a policy on how to deal with it, as long as we didn't have a direct superior of the two of us, we could do whatever we wanted. We had guidelines. It was the funniest thing.

Sal Daher: Also the propriety. Rich is not a masher type. He was what's known as an NJB, a Nice Jewish Boy, not likely to be doing that kind of stuff. [laughs]

Richard Lane: I didn't stalk her, matter of fact.

Sal Daher: Okay.

Richard Lane: We had a good time. We were friends for years before I even asked her out, but with the breakup of the phone company, and I did a lot of stuff on marketing. If I get too detailed, tell me to move quicker.

Sal Daher: Right

Richard Lane: They broke up the company and the cellular company got broken up into the seven Baby Bells. For those who didn't follow the industry like I, there was 22 operating companies within the AT&T infrastructure, the antitrust suit that they were fighting was settled in January 1982. They said certain companies are going to be in the different regions. NYNEX, if people remembered was New York Telephone, New England Telephone, then you had Bell Atlantic which was the middle Atlantic companies. Then you had PacTel which was Nevada and California.

Sal Daher: Basically what they did is they separated what was the utility aspect of it, which was the local landline business. Those businesses, they created these regional entities that were like monopolies. They had regional monopolies for the landline, but those individual companies like New England Telephone, which then became Verizon, they could go off and do different things and create different businesses on top of providing the landline service, which was considered a public utility. So Verizon became very big in the cellular space. Some of these other companies went in different directions.

Richard Lane: You actually said something that you didn't realize Sal, that was of super significance. When they announced divestiture, the thought was the local landline business would go to the operating companies. The new wireless technology was supposed to stay with AT&T.

Sal Daher: That's right.

Richard Lane: What happened is, Charlie Brown, during the McNeil Lerner Monday Night News was interviewed, and somebody asked him, at least this is how I remember it.

Sal Daher: Who's Charlie Brown? Not he of the Christmas tree and Lucy and the football?

Richard Lane: No, Charlie Brown was the chairman of AT&T at the time.

Sal Daher: Okay.

Richard Lane: He was interviewed and somebody said, "what about this new wireless technology?" He says, "That's for local phone calls. That will go with the local exchange companies." I having accepted my job in cellular that morning before the divestiture, and is sitting there saying, holy cannoli."

Sal Daher: Oh, no.

Richard Lane: [laughs] I'm not going to have a boss. [laughs]

"... It's a business that didn't exist. Before that, landlines were everything. It was everything, that was telephony was a landline..."

Sal Daher: In the original settlement, cell phones with AT&T were supposed to be like a nationwide monopoly in the hands of the AT&T?

Richard Lane: That's what the AT&T was thinking. Nobody ever addressed it because they didn't exist yet. Don't forget, the first cellular commercial call wasn't made until Columbus Day in '83. This is two years.

Sal Daher: October 12th of '83. It's a business that didn't exist. Before that, landlines were everything. It was everything, that was telephony was a landline. Unbelievable. Unbelievable. Tell me about how somehow you got into cell telephony in order to get to Jitterbug.

Richard Lane: I was brought into the group for cellular planning and I was the general manager of marketing. I did the marketing forecast. We had to design what a cellular system is. We now think of it as ubiquitous, but we had to build out towers, and to build out towers at the time was a million bucks a tower. We had to say, "Okay, what is the geographic area that we're going to try to cover?" There was 30 markets and those went to the seven Baby Bells.

Sal Daher: From AT&T, the original mother bell Ma Bell.

Richard Lane: It was broken up. U.S. West had a company and most of the companies following the entrepreneurial model that we did with the cellular planning company, we called it AMPS, Advance Mobile Phone Service. We said, "To make this work, you cannot be co-located with the wireline business." Most of the companies put them, not only were they separated, they were in different states. Southwestern Bell, the landline business was headquartered in Saint Louis, Cellular in Dallas, PacTel phone company in San Francisco, Cellular in Orange County, Southern California. We tried recommending that to every one of the seven companies.

Sal Daher: Was this like a regulatory thing or was it just like a strategic decision?

Pacific Telephone Company

Richard Lane: This is me and a group of what people say, "We're advising you as a company that this is what the best way to make it work."

Sal Daher: If you run it with your landline business, it'll never get off the ground because the landline people will perceive it as competition, they will squelch it. It's skunk work. Basically, you said you have to set up a separate skunkworks thing. This is one of the airplane manufacturers. The idea is that they had an independent group that had independent funding and did their own thing and with minimal supervision. That makes a lot of sense that they would hive them off because otherwise, the incumbent business would squelch the nascent businesses that in the beginning didn't look really profitable, but in the end, basically took over.

Richard Lane: I went out to PacTel, Pacific Telephone, or the Pacific Telesis as a parent was called and wrote the plan to build out the LA system as director of marketing. That once went over very well. I won't go through all my accolades, but they then asked me, "What should we do now?" I sat there, and I'm not an inventor, but I said, "Hey, Pacific Telephone, we're California--" At that point, we're Pacific Bell-- "we're California, Nevada Telephone Company. That's not an exciting business for the future, but we are going to just say we're heavily regulated. We're not allowed to make much profit. We have a couple of cellular properties. What are we?" They asked me to put together some thoughts and I did brainstorming with all the employees.

Now, remember, I was one of the seven original employees of that company. There were seven of us who started it on rented furniture. A little side note, because we were unregulated, we weren't allowed to use any of the money from the regulated telephone company. We had to raise our own money.

Sal Daher: What was the entity called again?

Richard Lane: The cellular company was called Pacific--

Sal Daher: No, no, no,-

Richard Lane: PacTel Mobile--

Sal Daher: -the original entity that was created out of AT&T.

Richard Lane: Oh, Pacific Telesis.

Sal Daher: Okay.

Richard Lane: PacTel Mobile Access was the cellular company.

Sal Daher: That brick phone that you had, who made that?

Richard Lane: Motorola. We were not in the equipment business.

Sal Daher: Motorola, okay, so this is like the original Motorola cellular phone. You have a copy of it that we'll make available and we'll put it in the video. Okay, Rich, with PacTel, is that where Jitterbug came in?

Richard Lane: No. Fast forward, PacTel I wrote the-- Let me just finish the PacTel. I wrote a plan saying we should be a nationwide telephone company based on wireless, and they made me CEO of that when I was 29. I was out of school two and a half years. The company recognized that the legacy people, the people coming out of the old twisted pair, what we used to call the landline phone business, were not going to be thinking out of the box. That's how I became a CEO at 29.

Fast forward, I came back east, I married my wife, I did a whole batch of things, and got brought up to stop being an intrapreneur and become an entrepreneur in Boston. I got the approach by Marty Cooper and Arlene Harris, long longtime friends in the wireless business. Marty Cooper with the phone I showed you, he made the first call in the history of the world on cellular. That's what he-- a replica of that--

Sal Daher: There was Columbus Day, 1983?

Richard Lane: No, that's the first commercial. He made the call on April 3rd, 1973. It was Motorola and AT&T were challenging each other. Marty called Joel, who's his counterpart at Bell Labs, and made the first call. For those who may have seen a Mazda commercial where you see somebody with that brick, that's what he was pretending to be. Marty and his wife, Arlene, who is the first woman in the wireless hall of fame, called me and I had been their second customer when they did their first business.

The Jitterbug

He said, "Rich, we think we thought there is a need for cellular phones for older people." I flew out to California and met with him and he said, "Rich, you just know how to build businesses. We know how to come up with concepts. We know how to get a team together, but we don't know how to hire people and do-- That's not our expertise." Again, going back to my comment, people do different things at different roles, and the same person can do different roles, but frequently, it's in different companies.

They said to me, "We have a vision." Arlene and I and Marty we are all recognized as pioneers of wireless, and Arlene's mother, and my mother wouldn't use a cell phone. We said, "Okay, we got to figure out why." I went out, commuted from Boston to San Diego for 13 months, and we got Samsung to build it. We designed it. We had an ear cup to keep the background sound. They were dial-tone so you didn't have to see any question-- I mean you didn't have to see any icons.

Sal Daher: Just to describe it, this is like a flip phone, a large flip phone with a rubber ring around the edges to keep the sound out, and big buttons that light up so it's easy for the senior person to see, even I could see it now, the Jitterbug.

Richard Lane: Everything was a question on the screen.

Sal Daher: You didn't have a million menu items, it was just a very straightforward question on the screen.

Richard Lane: It would say, "Do you want to make a call?" If you had voicemail, "Do you want to listen to your voicemail?" Then the buttons were, yes, no.

Sal Daher: Yes, no.

Richard Lane: Why send in for people don't know and send in was because--

Sal Daher: It's designed by engineers, user experience by engineers.

Richard Lane: It wasn't even that bad. Oh, the buttons were out of the two-way business, they were already on two-way-- on radios so they used the same buttons.

Sal Daher: Rich, let's summarize the Jitterbug experience. How many million Jitterbugs did you manage to sell?

Richard Lane: I did it for the first year. Got the first 50,000 phones out there, hired a replacement, and stayed as an advisor, and invested.

Sal Daher: Oh, you didn't want to go to California?

Richard Lane: Yes. My primary thing was, A, my family didn't want to move, but bigger was my mom who was at the time in her late 70s and a widow, I just couldn't leave her. I was the closest of the three boys and I needed to be near New York. Anyway. We started the business. We designed the phone, we designed the whole support system around an elderly person. We designed everything around a user experience, somebody 65, 75 would want to use.

We ultimately brought in a guy from Bell Mobility, David Eames, who was-- I would not say he could start a company but he knew how to build a world-class company. He built the company up. We had raised some money and then will give you an interesting thing on raising the money. Let me tell you that one first. I would go CPCs here in the Boston area when I would come back east because I needed to keep my network going. They'd say, "Oh, are you looking for money?" "No."

Charles River would say, "Do you need some money?" Bruce Sachs would say, "You need some money?" I said, "No. Let me tell you what we're doing." "You promised me when you need money, you'll come to us." It's always nicer to use us angels cause we had an angel investing at that point, it was Arlene's mainly, but we had angel people funding us to get us off the ground and kept telling the VCs, "We don't want you yet," because nothing a VC hates to hear more is that they're not critical to your success.

Sal Daher: Rich, let's just encapsulate the Jitterbug story.

Richard Lane: Okay. Arlene Harris and Marty Cooper asked me to look at the market for building a technology device.

Sal Daher: These are colleagues from PacTel?

Richard Lane: No. These are leaders in the wireless industry.

Sal Daher: These are two leaders in the wireless industry. They perceive the need for a cell phone for senior people. Arlene's mom didn't use a cell phone. Your mom didn't use a cell phone, and so anyway, she had this idea of creating Jitterbug.

"... A couple of things worth noting, a device around older people, needs to be looking at their user’s expectations. We're hardwired by the time we're 65 to think certain ways, to do certain traits..."

Richard Lane: Marty and Arlene, Marty, who is the former VP of engineering at Motorola, who invented the first cell phone. Arlene, his wife, who is the first woman in the wireless hall of fame, approached me and said, "Arlene's mother didn't use a cell phone. My mother wouldn't use a cell phone, but we were pioneers of the industry." It was an insult to us. We decided to develop a phone around the user experience of an elder person, putting dial tone in instead of an icon because they're used to a dial tone saying "Make a call." The idea was big buttons, dial tone, on-off button, everything that a normal 65 five-year-old, primarily woman, would be interested in a phone to make it easy to use.

Sal Daher: Rich is holding a Jitterbug in his hand and it's like an old clamshell flip phone. He had his rubber seal around the top half to keep noise out. Big numbers, yes, no buttons. You didn't need a dial button because you dialed when you heard a ringtone, it had a ringtone, which cell phones don't have because that's how landlines used to work. Anyway, you created a really attractive user experience for the older person, the older user as a transition, and you got people to use a cell phone.

Richard Lane: A couple of things worth noting, a device around older people, needs to be looking at their user’s expectations. We're hardwired by the time we're 65 to think certain ways, to do certain traits. This is physiological, not just--

Sal Daher: Right, crystallized intelligence versus fluid intelligence.

Richard Lane: Yes, and too many people think that old people are just stubborn. It's not that. They don't want to feel stupid because they can't, they also have bad tactical feeling. If you look at the button, this is volume. Why? Because people hold it here. They would hit the volume button. You had to move it away. You have to think about how it's used. The company of GreatCall, the creator of Jitterbug, was to create products designed around the elder user space. Let's get all technology available to them and then also let's develop products to help them age in place. The first two products were the phone and the Help, I've fallen button based on cellular technology. Those did not exist back then in 2005.

Sal Daher: Help, I've fallen.

Richard Lane: Those buttons were great when you're in the house, but when you went down and walked down the curb and you fell, there was nothing to help you. We created the five-star. Fast forward, they never went anything beyond that. I pushed and raised $200 million and tried to buy the company. This is me as an entrepreneur individual, just a shareholder of the company. They wouldn't sell it to me. I offered them $200 million. They wouldn't sell it. Good for me because what they did is they listened to what I was saying in the offer.

Why were they getting so little money outside? All these other bids came in under $200 million. They said, "Well, we got to reposition our business and focus on really the original vision of the company." They did that and in 2017, they sold the company for $425 million. A year later, Best Buy bought it for $800 million and for the first time proved that technology products designed around the elder market is significant.

Sal Daher: Awesome. Rich, is there room for a podcast appliance for older people?

Richard Lane: Yes, I got to figure out what it would look like.

Sal Daher: I'd love to have that so older people can listen because there's so many podcasts. There's millions of podcasts and I'm sure that if there was an easy way for them to have very-- Podcasts are still a little bit of a niche business. Adoption is still, I think, in the 30% of the population. We have a very dear friend who has been a technology founder for 50 years. He's invested in hundreds of tech startups, founded dozens of tech startups, he's very wealthy, and so forth. He has been on this podcast. He never listened to his podcast until he bought a new car that had a podcasting device on it. He just pressed the button to look for his podcast because he could never figure out how to get his own podcast. That's how many--

Richard Lane: Can I--

Sal Daher: I'm not going to mention names, but it's a dear friend of both of us.

Richard Lane: I think I know who you're talking about and I'm going to make a confession very privately. I don't want-- everybody turn off your podcast for two seconds. [chuckles] I've never been able to figure out how to listen to a podcast. You're going to have to tell me how to do it, because never --

Sal Daher: You're going to have to figure out how to do it. No, can we leave this in? Because this is a--

Richard Lane: Yes of course you can.

Sal Daher: We're going to leave this in Raul.

Richard Lane: I have spent my entire life on technology programming computers since 1970, when I programmed in Fortran, just to give you an idea how much older I am than you.

Sal Daher: I programmed in Fortran. I was in IBM 1130 when I was at MIT in '73, '74.

Richard Lane: So we're the same age. This was when I was in high school.

Sal Daher: Yes [crosstalk] I'm 67. Stack of cards.

Richard Lane: You're much younger than me. I'm 68 [crosstalk]

[laughter]

Sal Daher: Anyway, 2017, they sold for 400 million, and then eventually Best Buy, bought it for 800 million and it proved that there was a market for dedicated devices for older people. This put a bug in your ear about creating products for the elderly population.

Richard Lane: Yes, and I started doing that in 2005 when I was doing the Jitterbug and I've stayed passionate about it. I've been working with some venture people who are looking to fund companies doing this. I had a vision that I wanted to use for launching when I tried to buy GreatCall. I went and started to look at what can I do. I created a company.

Sal Daher: GreatCall was the company that owned the Jitterbug cell phone for elders.

Richard Lane: Right. Then I started a company called LifePod.

LifePod

Sal Daher: I was an investor in LifePod. Briefly tell us the LifePod story here. What was the original concept, how things developed, and then ultimately what happened?

Richard Lane: Okay, thanks Sal, and again thanks for your support in the company. When we originally started the company the idea was how do I automate using proactive speech? The TheLifePod unit would wake up and ask mom a question rather than waiting for mom to trigger a question.

Sal Daher: The problem was solving is that there are a lot of seniors aging in place. They have loved ones who are concerned about them but might be in another state, in another city, or just another part of town, they can't be there all the time, they might be working. You have a device that's resident in the home with the senior who is aging in place and it interacts with the senior at stated at times which can be programmed by the caregiver just to kind of monitor and make sure that things are okay.

Richard Lane: Right. It was a--

Sal Daher: Then get the caregiver involved if there's any sign that things are not okay.

Richard Lane: Yes, a question might be, "How did you sleep last night?" and then they said, "Not well," or, "How are you feeling?" "Not well," it could trigger a response, "Would you like Richard to give you a call?" If they said, "Oh, I'm feeling great," no need to have a follow-up call. Those are examples, routines, and so forth. The original concept was to design this as a two-way consumer to the caregiver similar to Jitterbug of selling it into their family saying, "This is something to help you take care of mom and dad."

In raising money, we got our lead investor buy a strategic who provided tens of thousands of Medicare Medicaid patients and then looking at it as a cost reduction of their internal staffing needs.

That was a totally different script, a different diagnostic. It had different regulatory requirements like HIPAA because in a family, you don't have HIPAA. When you're dealing with a public funded healthcare provider, you have to put all this in, and therefore the company took a pivot towards the institutionals, but that's a lot of buy-in from all the people in the bureaucratic as we talked earlier when we were looking at big companies and starting companies, this was a hard innovation versus what we were. It ultimately led to --

Sal Daher: They launched into a medically supervised innovation instead of a lightweight home extension of home caregiving

Richard Lane: Caregiver in a box as I like to call it.

Sal Daher: Caregiver in the box like a trip wire to know when the caregiver has to-- LifePod, yes, I see that. You have the actual device. That's the fourth prop, Rich. I want you to have your props lined up in front of you when we do the video, okay?

Richard Lane: I got it.

Sal Daher: Anyway, the lesson there was you needed to pay a whole lot more attention about the purpose, the motivation, what it is that the strategic partner wanted from the product versus what you your vision for the product was. Ultimately, your vision for the product was very different from the vision of the strategic player because they had their own constituencies to serve and it didn't work out. It was not a successful venture and you gave it your best. A lesson learned and I think it was a valuable lesson. Looking forward, what things are you working on?

Richard Lane: I'm right now working on other technologies to help people age in place. There's a couple of venture firms that I've been dealing with who are focused at this area, one of which Third Act Ventures. I'm also looking at, believe it or not, one of our LifePod investors invested because of the vision that I had. He then started doing stuff in that space and he's asked me to come help him. Right now, what I'm doing is helping other people who are trying to figure ways to help older people age in place, family members, allowing them to use tools to take care of their loved ones, whether they're professional caregivers like Bayada Health, which is a home nursing, or whether it's you and me taking care of mom and dad.

Sal Daher: Creating tools to amplify the capacity-- It was a force multiplier for caregivers whether they're professional or family providing care to their family members.

Richard Lane: Now, there's one other criteria in that which is, to me, extremely important. The wealthy people, don't mean to be derogatory to you and me, but we can hire people to do some of this stuff.

Sal Daher: That's right.

Richard Lane: The masses, not the top 1%, even the top 25% can probably make two. I'm focused at what can we do for the middle 50% from the 25. The people below 25, they can barely worry about food. I'm worried about 25% to 75%, that sector of the population. How do they take care of their families because they're the ones with the least amount of resources and the most need.

Sal Daher: How to create products that make their lives easier and improve the quality of care given to the seniors in their lives.

Richard Lane: Right. The other thing that you have to worry-- everybody's now talking senior care because the worldwide aging population, it was highlighted from COVID, one of the things that too many people are doing are widgets. I'm going to do one thing. That's all I'm going to do. I'm going to do diabetes monitoring or I'm going to do dementia tools.

Sal Daher: I'm going to do a podcast appliance [laughs].

Richard Lane: Yes. What happens is it is too complicated for people to integrate a solution. Where I come in and I help companies is how do we pull that together and create a platform that allows them to holistically look at multiple things? That, to me, is where the industry has to be going. If you're an entrepreneur, don't come to me and say, "I've got the best way in the world to tell you if mom fell." That doesn't do any good if she's got a urinary tract infection and you're not looking for that because that's the second largest reason. Somebody ends up in the hospital. If you have a separate system that does full detection and urinary tract infections, you haven't yet solved my problem.

Sal Daher: You need to be able to integrate all these systems.

Richard Lane: Yes. There's companies like Origin Wireless and so forth, they have the technology. They don't have the experience with the elder care to do it themselves so people like that partner. I think that's a Series A, Series B funded company and I think it'll be very successful cause they understand that they're a technology company, not a solution company.

Sal Daher: Okay. Rich, let's just wrap here. If you want to give us some of your parting thoughts.

Parting Thoughts to the Audience

Richard Lane: My parting comment, I always tell entrepreneurs that to be an entrepreneur is you're mentally healthy and you want to know what it's like to be bipolar. You're going to have high days and you're going to have low days, and you need to have people who are supporting you on those low days. It's easy to say on a high day, "Life is wonderful," but you as the founder have to be prepared emotionally and have the resources to help guide your team through those tough times. There's nobody--

Even Elon Musk has tough times. We have friends in common. He has days no different than you as a founder where he's pulling his hair out trying to say, "How am I going to make the next payroll?" when he started. This is not easy and you can't expect your customers to tell you what they want because as the old adage goes, "If Henry Ford listened to people we would have faster horses instead of cars."

Sal Daher: Exactly.

Richard Lane: That's my parting wisdom. I would love to hear from people. If they want help, I'm happy to help.

Sal Daher: Awesome. Richard Lane, entrepreneur, founder, angel investor, and Walnut buddy. Thanks for making time to be on the Angel Invest Boston podcast.

Richard Lane: Thanks for having me.

Sal Daher: I'm Sal Daher. Thanks for listening. I'm glad you were able to join us. Our engineer is Raul Rosa, our theme was composed by John McKusick, our graphic design is by Katharine Woodman-Maynard. Our host is coached by Grace Daher.